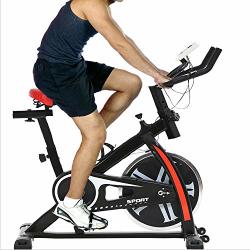

It requires in-home delivery, a process I went through twice because the first Peloton that was delivered physically locked up when I started riding it. This is not something you assemble at home, either. It’s nicely constructed and, at 135 pounds, so heavy that I needed help moving the bike around my apartment. It’s a carbon steel and aluminum bike with a weighted flywheel in the front that determines the level of resistance while you’re riding. The Peloton bike is like a Spin bike, although “Spin” is trademarked, so let’s call it an indoor cycling bike. Almost everyone I talk to, though, suggests that Peloton is capitalizing on a kind of perfect storm of bigger trends: the obsession with cycling communities like SoulCycle, the proliferation of screens and Wi-Fi connectivity in our lives, and a growing emphasis on health and “wellness.”Ī selection of on-demand cycling classes on the Peloton console, lead by instructor Alex Toussaint. Some people - including Peloton’s Feng - seem hesitant to call it a “fitness” company, probably because fitness fads come and go fast.

But like a lot of tech companies, it makes money off of the subscription it sells. It does sell hardware: that expensive bike and touchscreen console. When I’ve asked customers and investors over the past several weeks whether they see Peloton as a hardware company, a services company, or a fitness company, I’ve heard a variety of responses. In February, the company said it had 285,000 users, including bike owners, mobile app users, and in-studio riders. Since that first bike sold, the company has grown more than 200 percent year over year, according to its chief technology officer Yony Feng. first came into existence in 2012, but didn’t sell its first internet-connected, indoor cycling bike until 2014. The Peloton studio in New York City, where all of the live videos are streamed from. Such is the craze, I’ve learned, that is Peloton. Also, she has since become a certified cycling instructor. On April 25th, it will be her one-year “Peloversary,” she tells me. On three occasions she has made the seven-hour drive to the company’s studios in New York City, where the videos stream from, to take a class in person. Not only does she ride the bike daily, but she sometimes takes multiple live classes in a single day. So she made a deal with herself: if she could sell enough personal items on eBay within six weeks to cover the cost of the bike, she would get it. With an upfront cost of nearly $2000 for the bike itself, and a required monthly subscription fee of $39 per month for the exercise videos, Getty hesitated she had just spent $1,500 on a treadmill that she wasn’t using.

Then, a little over a year ago, Getty’s husband saw an ad on television for an Internet-connected stationary bike with a giant touchscreen attached to it, one that would live-stream classes into their living room. I tried running for awhile but it was always more of a chore, like ‘ Ugh, I have to go out and run five miles today.’” “As far as my fitness level, I’m kind of an all or nothing person,” Getty told me over the phone. The 50-year-old copywriter from Champlain, New York, had never been so enthused before about exercise. At some point last year, Lisa Getty decided it would be fun to take a dozen different indoor cycling classes all in the same day.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)